in The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories

INTRODUCTION

Generally speaking, politics is a set of principles, beliefs and activities associated with the distribution of power and resources. In terms of relations among states, communities, organisations or individuals, the aim of politics is to influence decision-making processes that help to improve someone's status and/or to increase their power.

In this sense, translation is very much a political act. Translators are traditionally viewed as being invisible and passive, working behind the scenes to transfer information from one language to another. However, in recent decades, researchers are increasingly investigating the politics of translation and the (pro)active role that translators may play in cross-cultural communications.

Specifically, to translate a text from one language (“source”) to another language (“target”) is to make it not only exist but also accessible to readers in the target culture, and therefore empowers that text to impact the target cultural consciousness in myriad ways. Here, “cultural consciousness” is defined as our awareness of how our own distinct culture shapes our beliefs and behaviours while influencing our perception of those from other cultural backgrounds.

More importantly, as a political act, translation makes the perspective of an author – shaped by their experiences and interpretations of the norms and values of the source culture – accessible to readers in the target culture. Such access may affect how these readers engage in conversations not only between the source and target cultures but also within the target culture itself. The fact that an author's perspective is accessible to readers in other cultures through translation may also affect their reception by readers in their own culture.

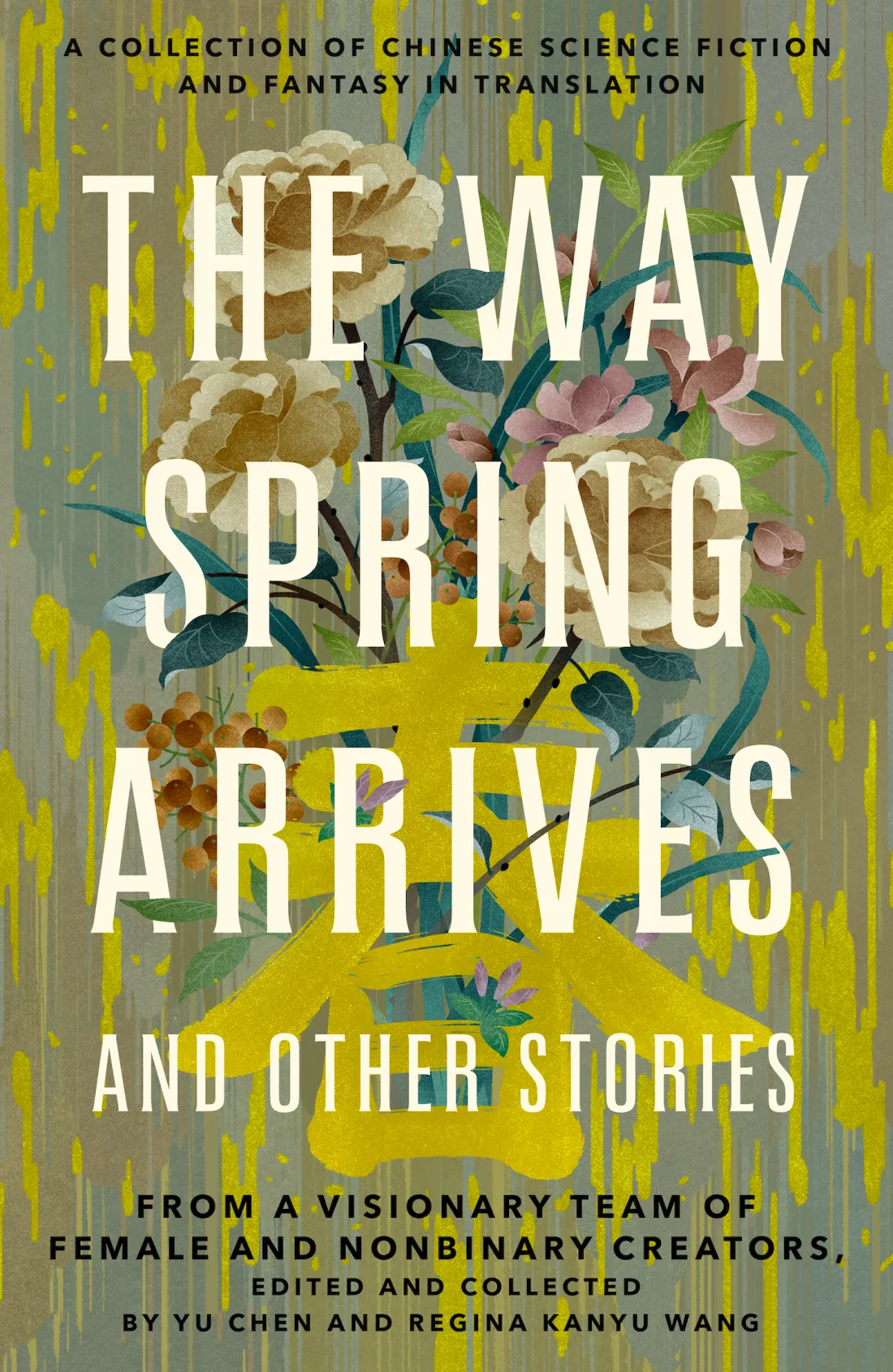

A case study at hand is The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories (Tor Books, 2022), which features “imaginative stories and compelling essays written by 28 award-winning authors, translators, and scholars”. The book's dust jacket explains: “Written, edited, and translated by a female and nonbinary team, these stories have never before been published in English and represent both the richly complicated past and the vivid future of Chinese science fiction and fantasy.”

This article explores the politics of translation in The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories, from the book's inception to its publishing process, its selection and arrangement of stories and essays, the translating approaches discussed by some of the translators, and, finally, the translating strategies and choices revealed in some of the stories. As the following demonstrates, this book is not merely a product of cross-cultural interactions where translators served as neutral intermediaries facilitating communication between people who do not share the same language. Instead, it is part of a purposeful process where its publishers, editors and translators set out to shape the cultural consciousnesses in both the source and target cultures.

PUBLISHING PROCESS

In a conversation with Arley Sorg via Clarkesworld (Issue 186, March 2022), Regina Kanyu Wang and Yu Chen, editors of The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories, mentioned the book's inception in 2019 as a collaborative project between Storycom and Tor. Wang has been working as Overseas Market Director for Storycom International Culture Communication Co., Ltd. since 2016, and introduced the company as “the first professional story commercialisation agency in China”. In her words:

Storycom had been in partnership with Clarkesworld [since 2014] and published dozens of Chinese science fiction stories translated into English. We were all excited about the idea of an all-female-and-nonbinary anthology of Chinese speculative fiction in translation.

In the selection process, Yu made the recommendations while Tor's Lindsey Hall and Ruoxi Chen provided feedback. In the end, 17 speculative stories by 15 authors were chosen. Each story was matched with a “suitable” translator and “we are happy about the chemistry between the original stories and the translations”, explained Wang. Also included in the collection were five essays covering subjects such as writing, translation, publishing and reading speculative fiction in China.

This combination of stories and essays allows The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories to stand out among contemporary efforts to introduce Chinese speculative fiction to anglophone readers via translation. In order to offer “a gateway to a larger context with multiple layers and plural extensions”, the book's stories and essays – as well as the genres of stories – were prudently organised so that “if you read carefully, you can see that all the pieces are ordered in a way that [they] form a larger narrative”.

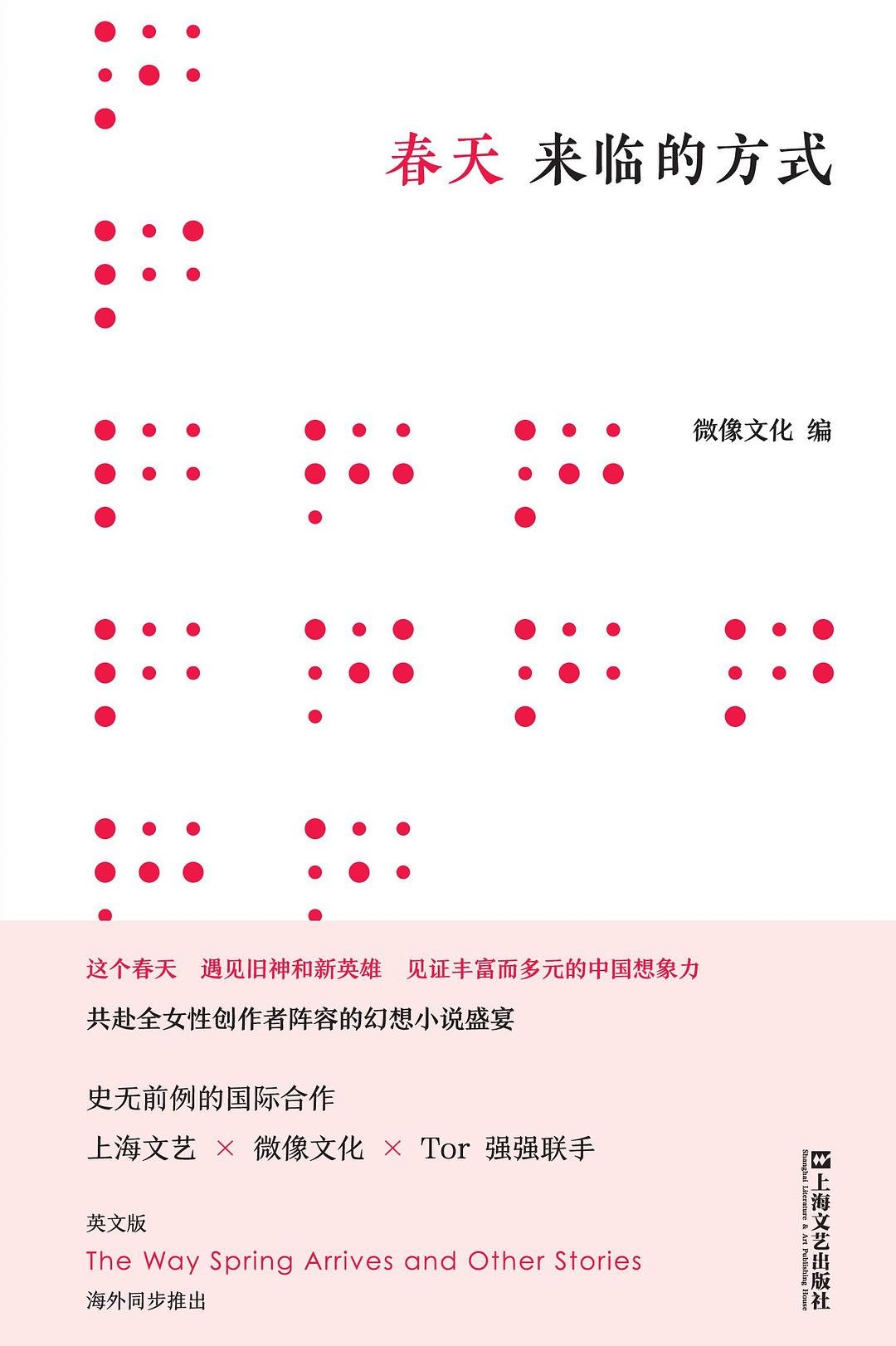

What makes the translation project even more unusual is the simultaneous publishing of the book's English and Simplified Chinese versions. With that said, Chuntian lailin de fangshi (春天来临的方式), published by Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House slightly earlier than The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories in 2022, is quite different from its English counterpart. While the Chinese book contain the 17 stories originally written for Chinese readers, it includes the Simplified Chinese translation of only one essay. (In fact, Xia Jia self-translated her story “What Does the Fox Say?” from English to Simplified Chinese, but that is another story to be explored in the near future.)

In addition, the cover of the English book has “showy eye-catching flowers...combining the beauty of Chinese traditional art with the fashion of Western modern design”. Wang specifically highlighted China-born, New York-based cover artist Feifei Ruan, who was commissioned by BBC Studios in 2018 to create a set of illustrations featuring the TARDIS at seven Chinese locations to promote the famed TV series Doctor Who in China. In contrast, the Chinese book's cover designer Zhu Yunyan initially attempted combining “Chinese brush painting with Western photography”, but settled instead on a “minimalist style”. As a result, the cover of the Chinese book features “gilded red dots, which is the binary code of the book title, and binary code is considered to be the language that aliens can understand” as Yu described it.

Perhaps a combination of traditional Chinese and modern Western design elements was presumed to be appealing to those anglophone readers interested in reading Chinese speculative stories in translation, while visual representations of certain aspects of (Western) science and technology were presumed to be attractive to Chinese fans of science fiction in general? This question deserves further investigation by book design specialists in both languages and cultures.

“GOING GLOBAL”

On the cover of Chuntian lailin de fangshi, the simultaneous publishing of The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories as its anglophone counterpart is touted as an “unprecedented international collaborative project”, a “brilliant debut of Chinese speculative literature 'going global' in recent years, marking another new attempt for Chinese science fiction to 'go overseas'”.

As Jing Tsu points out in her essay “The Futures of Genders in Chinese Science Fiction” in The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories, science fiction writers in China “are increasingly in the political limelight for how they can play a role in China's ongoing ambition to lead the next technological wave, helping to enhance the country's cultural image globally”. This observation on China's zou chu qu (走出去) or “going global” ambition is backed by Tsu's reference to the Kehuan Shitiao (科幻十条) or “Ten Points Concerning Science Fantasy”, a set of policies issued by China's National Film Administration and the China Association for Science and Technology in August 2020 aiming to “push the development of sci-fi intellectual property in the [country's] film industry”.

Specifically, since a delegation from China attended the World Science Fiction Convention for the first time in September 2012, Chinese writers have been hard at work in their ambition to make the country a “Great Nation Rising in the World of Science Fiction” as declared by Chen Qiufan via cn.NYTimes.com. The year 2012 marked the first time a China-born sci-fi author was recognised in the West, with Ken Liu's “The Paper Menagerie” winning the “Best Short Story” title in both Hugo and Nebula Awards. However, it is Liu Cixin's The Three-Body Problem winning the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel and Hao Jingfang's “Folding Beijing” winning the 2016 Hugo Award for Best Novelette that truly launched Chinese science fiction to the international stage.

By February 2014, the translation and publishing of The Three-Body Problem in English and the adaptation of Ted Chiang's “Story of Your Life” as the film Arrival were well under way. The term “Chinese-style Science Fiction” was coined that year by the Chinese newspaper Spring City Evening News in its celebration of “a kind of science fiction belonging to the Chinese people” created by Liu, Chiang and other “Chinese” authors:

This kind of science fiction is characterised by its display of prominent Chinese features. Whether it is the characters Han Xin and Su Qi in Qian Lifang's The Will of Heaven and Mandate of Heaven, respectively, or the background of the start of Liu Cixin's The Three-Body Problem, they are all influenced and inspired by Chinese history and culture. Even Chinese-American author Ken Liu has perfectly merged science fiction and Chinese culture in his “The Paper Menagerie”. It can be said that, different from their Western counterparts, the way of thinking in works of science fiction by Chinese authors and overseas-born authors of Chinese descent is Chinese. The great Chinese culture has marked their writings with a vivid brand that is distinct from Western science fiction.

Fast forward to 2020, when the “Ten Points Concerning Science Fantasy” were unveiled, and three anthologies of contemporary Chinese science fiction had been published in English – Invisible Planets (2016), The reincarnated Giant(2017), and Broken Stars (2019). Considering such success, as well as bestselling films such as The Wandering Earth, Ne Zha, White Snake and The Legend of Hei – all of which premiered in 2019 – there is no surprise that the “Ten Points” as policies demand the Chinese sci-fi film sector to “increase efforts to cultivate science fiction film scripts, encourage and support original creation, promote the transformation of science fiction literature, animation, games and other resources, enrich the source of innovation in science fiction film content, and promote the establishment of a multi-level, diversified and sustainable science fiction film script supply system”.

The political focus of the “Ten Points” was highlighted by journalist Rebecca Davis in her article “China Issues Guidelines on Developing a Sci-fi Film Sector” in August 2020 via Variety:

To make strong movies, the document claims, the number one priority is to “thoroughly study and implement Xi Jinping Thought”. Based on the Chinese president’s past pronouncements on film work, filmmakers should follow the “correct direction” for the development of sci-fi movies. This includes creating films that “highlight Chinese values, inherit Chinese culture and aesthetics, cultivate contemporary Chinese innovation” as well as “disseminate scientific thought” and “raise the spirit of scientists.” Chinese sci-fi films should thus portray China in a positive light as a technologically advanced nation.

This emphasis on Chinese sci-fi films showcasing “Chinese values, Chinese culture and aesthetics, and contemporary Chinese innovation” corresponds with the aforementioned “Chinese-style science fiction” that draws influence and inspiration from Chinese history and culture. Not surprisingly, contemporary discussion in China on Chinese speculative fiction “going global” consistently and continuously focuses on telling “Chinese” stories. Examples range from how to define “Chinese science fiction” to the types of “Chineseness” constructed for local/Chinese and international/Western/anglophone audiences, to the strengths of genres such as science fiction and fantasy in helping to promote Chinese films overseas, and then to successful Chinese IPs such as films New Gods: Nezha Reborn (2021), Creation of the Gods: Kingdom of Storms (2023) and Ne Zha 2 (2025), video games Genshin Impact, Black Myth: Wukong and Naraka: Bladepoint, Pop Mart's Labubu dolls, and how JKSManga's web novel My Vampire System (2020) is “inspired by Chinese internet literature and Chinese culture”.

TELLING “CHINESE” STORIES

Against this background, it came as no surprise that in their selection of stories and essays for “an all-female-and-nonbinary anthology of Chinese speculative fiction in translation”, editors Regina Kanyu Wang and Yu Chen concentrated on finding “good stories”. More specifically, they tried to select “stories that are deeply rooted in the Chinese or larger Asian context” as Wang described it in the aforementioned conversation with Clarkesworld. Yu further elaborated:

The one more important criterion was to find good stories. For translated works, you may lose the verve of Chinese language, or misread the cultural background, these things are inevitable, but a good story can be popular all over the world. The other most important criterion was the Asian background. We gave up some wonderful stories that were clearly influenced by Hollywood films, and instead we chose more stories that retell myths and legends in order to show our long history and diverse cultures.

Note the use of the word “Asian” here, as it is not found anywhere in either The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories or Chuntian lailin de fangshi. The word was used again in Wang's discussion about Shen Dacheng's “Blackbird”: “[It] is a story about death. In Asian society, women are always afraid of getting old. You see advertisements of young beauties without any wrinkles. Actresses who are above their thirties can hardly find any characters that are suitable for their real ages. The protagonist's resistance of death and elegant gestures in a nursing home implies this age anxiety in Asian society.” When asked about stories that might surprise anglophone readers, Yu used the word yet again: “'Surprise' often means new experiences and broader boundaries. There might be some 'surprise' in plots, or words, or backgrounds, especially in some typical Asian stories. For instance, the story of [Shen Yingying's] 'Dragonslaying' happens in the Chinese fantastic worldbuilding Yunhuang (云荒), while [Count E's] 'The Tale of Wude's Heavenly Tribulation' is related to traditional Taoist culture.”

If the terms “Chinese” and “Asian” can be interchangeable – or, if “Chinese” is considered to be representative of “Asian” – then what specifically defines and/or merits the stories in this collection as “Chinese”? More importantly, how is translation facilitating the presentation of these “Chinese” stories to anglophone readers who may or may not be familiar with Chinese history and culture?

As previously mentioned, translators are traditionally viewed as invisible conduits of information between languages. They are expected to remain neutral, staying true to the source texts while ensuring the target texts read fluently and reflect faithfully the styles and perspectives of the authors. However, in reality, because languages evolve constantly as mirrors of their cultures, the translating process inevitably has to be flexible as translators find strategies to cross or at least narrow the cultural gaps while meeting the structural and even ideological demands of both the source and target languages. Translation is therefore a result of long processes of purposeful decision-making, with translators taking a (pro)active and often political role in their attempts to most satisfactorily represent the authors of the texts in their charge.

A translator's decisions and strategies in translating a text are rarely visible to its author in the source language and its readers in the target language. Unless one is both able and willing and can afford the time and energy to study the source and target texts side by side, it is often the case that even editors of a translated work remain unaware of the subtle and often hidden differences between them. The more common approach in the publishing industry is for editors in the target culture to peruse the translation and ensure its content is suitable for readers of that cultural background. To save precious time, manpower and resources, a proofreader or a second translator's opinion is seldom sought.

Of course, this is not to imply in any way that the editors of The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories were negligent in their work. Instead, it is thanks to their decision to include three essays where translators discuss their craft that we get a rare glimpse of the politics of translation in this collection. Two particularly illuminating examples are Yilin Wang's “Translation as Retelling: an Approach to Translating Gu Shi's 'To Procure Jade' and Ling Chen's 'The Name of the Dragon'” and Rebecca F. Kuang's “Writing and Translation: A Hundred Technical Tricks”.

Wang's suggestion that modern retellings of ancient myths and folktales “can offer new insight into the stories they're derived from” is a familiar notion among anglophone readers of speculative fiction, especially fantasy. Her emphasis on the potential of a translation to “deepen or challenge readers' understanding of the source texts, the source and target languages, and even storytelling itself” is insightful, shedding light on the nature and significance of translation as a political act.

In comparison, Kuang, wearing multiple hats as writer, translator, academic and Chinese American, makes this observation:

I am still struggling to figure out how to position myself as a Chinese American novelist and translator, and to navigate the disparities in power and privilege that entrails. And I still struggle with balancing my sense of the author's voice and my own authorial voice, which is particularly difficult when one sometimes forgets which is which. The ability to dance between languages and literary environments is a privilege, and one that can harm and offend if carelessly used... When moving between languages also involves moving between worlds, perhaps it helps that the translators, too, are people who are used to being on the outside, who are used to navigating hidden spaces, and who are familiar with the challenge of making themselves understood.

Kuang asserts that “writers and translators must both carefully consider who they are writing for, and how they represent a culture that is not their own”. Between the two approaches – transplanting a “Chinese” story into a Western linguistic and cultural environment in order to make it relatable to anglophone readers, or preserving as much the “Chineseness” of a story as possible and making Chinese history and culture seem more Other than it is – there are complexities and nuances that translators from both the source and target cultures have to consider on a context-dependent and case-by-case basis. The same applies to writers and publishers in their efforts to help “Chinese” speculative fiction “go global”, where a balanced approach is required between emphasising the “Chinese” characteristics of science fiction and fantasy stories and highlighting the universal values they convey.

GENDER MATTERS

Interestingly, in her aforementioned essay “The Futures of Genders in Chinese Science Fiction”, Tsu further argues: “If today's sci-fi writers decide to seek new linkages with China's past, it is not for the sake of a nostalgic return but to reinvent a path of discovery through myth and folklore.” Because “science fiction does not just traverse genres; its community and readership have always been global, real and imagined”, the author appears to be signalling the strengths of speculative fiction in launching dialogues between the “Chinese” and the universal, and between the traditional and contemporary.

For the purpose of discussing the politics of translation in The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories, Tsu's conclusion is worthy of being quoted at some length:

Authorship in contemporary science fiction is not just about gender, but invokes broad questions about the scientific and technological conditions of our times. The milieus we now experience demonstrate that diversity and plurality are simply facts of reality, not the result of preferential choice... Under such circumstances, one wonders what a gendered approach to reading and understanding Chinese science fiction entails. One thing is certain: What goes into it is no longer a literary affair, if it ever was.

In a landscape that is technological and political, inspirational and practical, Chinese science fiction...cannot be treated as simply fiction, but instead as a barometer of our times, replete with our own anxieties and hopes about technology, enhanced by new tensions in global geopolitics... For the first time, readers should no longer hope to simply lose themselves in the fictional world created by the author, but also ask how the author themselves got into fiction, and what the larger, complicated landscape is that Chinese science fiction is compelled to navigate.

This observation is crucial in our understanding of contemporary Chinese speculative fiction from outside of China, how Chinese sci-fi and fantasy authors are shaped by their own culture, and how they seek to inspire or challenge the perception of that culture by their readers. More importantly, in this “larger, complicated landscape” that is the global community and readership of speculative fiction, not just authors but also translators play a vital role in their attempts to confront and contest our consciousnesses, how we perceive other languages and cultures as well as our own.

A good example is Yilin Wang's translation of Gu Shi's “To Procure Jade”, where the gender-neutral pronoun “they” is used when referring to the protagonist, a former eunuch of the Qing Dynasty. As the translator explains it, this translation choice “can serve as a reminder of the often overlooked history of gender-neutral pronouns in Mainland China, and of how nonbinary characters in ancient Chinese tales may have been erased due to the loss of gender-neutral pronouns”.

Another example is Emily Xurni Jin's translation of Shen Yingying's “Dragonslaying”, where the gender-neutral pronoun “they” is used in depictions of the creature jiaoren (鲛人), half-fish beings that have long left their mark in mythology and romantic folklores of both ancient China and the fictional world of Yunhuang. In the source text, the young jiaoren undergoing the intricate “dragonslaying” procedure while being observed by a woman physician is identified as “she/her”, and the character's fate is compared to that of the physician and her fellow females struggling for recognition and respect in their patriarchal society. However, in the target text, the use of the pronoun “they” not only foreshadows the horrid circumstances in which the “dragonslayers” are forced to live but further highlights the unjust treatment of the jiaoren as a whole species.

Curiously, at the end of the story “Dragonslaying”, one sentence from the source text is missing. Here, the protagonist gazes at the “indistinct sparks of firelight” twinkling on a distant beach in the darkness and recalls the local custom of launching festivities whenever one or more jiaoren are captured. Knowing these beautiful creatures can be sold, for considerable rewards, as “concubines, dancers and whores” to the rich and powerful, she thinks “perhaps [the firelight] was the fishermen's bonfire, celebrating a good catch”. As the comparison below demonstrates, the omission of one particular sentence (underlined) from the target text considerably diminishes the effectiveness of the story's subtle yet significant conclusion in the source text:

Source Text by Shen:

那火光开始只是一点两点,后来就连成线,像一个变形的 “人” 字。再后来就愈来愈盛,一直蔓延到南方碧落海的深远处,融入一片无涯的星海。

Target Text by Jin:

The firelight was a few scattered spots at first, but then more lit up, gradually forming a few lines, extending all the way south into the depths of the Biluo Sea – the blazing trails of fire melted into a boundless sea of stars.

Target Text by this reviewer:

The firelight began as a few dots, then connected into lines, resembling a deformed character “human/mankind (人)”. Then it grew stronger, spreading south into the depths of the Biluo Sea, merging into a boundless sea of stars.

Perhaps not surprisingly, “Dragonslaying” is not the only story in The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories where the content is altered in its transfer from the source text to the target text. Other examples – which are too many to be analysed in this article – range from minor changes of paragraphs, sentences and phrases to major modifications of story titles and even story structures. The former may be mistranslations due to errors or a lack of understanding of linguistic or cultural nuances. The latter, however, may or may not be results of deliberate translation choices intending to help anglophone readers understand the stories that were originally written for Chinese readers.

Finally, it is necessary to mention once again Jing Tsu's aforementioned piece, as it is the only essay included in Chuntian lailin de fangshi. Originally written in English, the title of the source text “The Futures of Genders in Chinese Science Fiction” is changed to “Xingbie goujian yu Zhongguo kehuan de weilai” (性别构建与中国科幻的未来) or “Gender Construction and the Future of Chinese Science Fiction” in the target text. Considering the essay is placed at the end of the collection as an “afterword”, the mistranslation of its title seems particularly remarkable. As the comparison below demonstrates, there is even a difference between the source and target texts of the essay's conclusion:

Source Text by Tsu:

Gender, as with genre, is a question that has been and will continue to be reinvented with new stakes. While Chinese science fiction is still a young genre, it will surely intrigue readers in provocative ways, inspired by what we hope the world will become.

Target Text:

性别问题,和类型问题一样,是一个常问常新的问题。作为一个新兴文类,中国科幻将会以各种新奇的方式吸引读者,不断启发我们对未来世界的思考。

Target Text translated back to English:

The question of gender, like the question of genre, is one where constant inquiries lead to new insights. As an emerging literary genre, Chinese science fiction will attract readers in a variety of novel ways, constantly inspiring our thinking about the future world.

Intriguingly, although both the source and target texts of this essay have clearly identified Chuntian lailin de fangshi as “the first all-female-and-nonbinary anthology of Chinese speculative fiction”, the collection has been promoted by its publisher and widely perceived by readers across China as an anthology of Chinese speculative stories planned, selected and edited by “an all-female team”. We are thus reminded of Tsu's observation, that “Chinese science fiction has yet to articulate its rightful place in the contemporary world, and is pulled in different directions”. The politics of translation has certainly influenced the production of The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories and Chuntian lailin de fangshi as two distinctly different books.

Christine Yunn-Yu Sun is a Taiwan-born Australian writer, translator, reader, reviewer, journalist and independent scholar in English and Chinese languages.